2: Building the Whole Product

So you think you know what a product is. It’s more complicated than you think.

Ask someone to describe a product and they will normally describe its physical attributes, perhaps how it works and what it does for them. “I know it when I see it,” to borrow the phrase used in 1964 by United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart presiding in the famous Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964) case.

But there is a lot more to a product than meets the eye. Theodore Levitt, who I mentioned in Chapter 2 in connection with FABs, conceived the ‘Whole Product Model’. In this assessment, a product is the sum of four elements:

- Generic product

- Expected product

- Augmented product, and

- Potential product.

The Generic product is the set attributes you that together make up the core. The Expected product is the solution – or set of benefits – a user expects to get from it. The Augmented product, which arises when your product is combined with others from third parties, like accessories. Finally, the Potential product occurs when the product is combined with upgrades or add-ons, which could become available some time in the future.

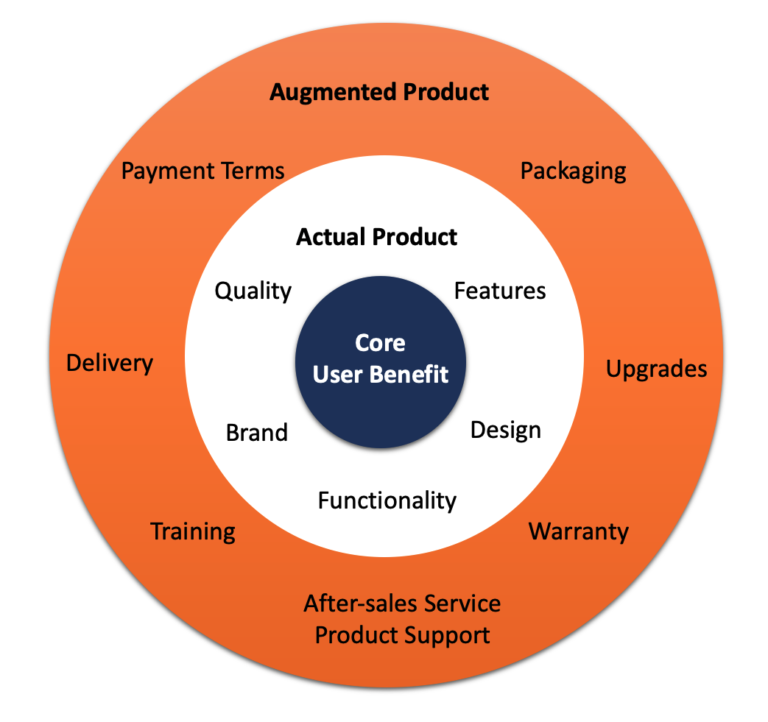

There’s a simpler way to conceive of a product in a three-layer model:

Core product: the essential benefit the user derives from using the product;

Actual product: the array of features and functionality which define the product and differentiates it from others in the same category.

Augmented product: a broader set of added features which enhance the value of the product to the user.

The Core product is the basic thing you buy: a pen to write with, a car to get you ‘from A to B’, a smartphone to make calls and browse the Internet, a server to store files.

The Actual product comprises the features, attributes of its functionality, and the quality of its manufacture. This includes includes the brand. People will buy a particular brand of product because it means something to them: practicality, innovation, style, exclusivity, quality, cachet – it can be one or many things. It’s personal. In consumer packaged goods (CPG) AKA fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) markets, people buy brands because friends, family, and opinion formers they trust recommend the brand, or owning a branded product tells others about their personal values and social aspirations. In the business to business (B2B) context, the brand may come from a supplier on the approved vendor list (AVL) qualified by the corporate purchasing department.

The Augmented product includes an array of features which enhance the experience of buying and using it. Design (functional or innovative), payment terms (pricing per each or in bulk, discount for cash, by app or credit credit card, by installments), packaging (bag, box, carry case, dispenser), delivery options (a preferred shipping carrier, pick up at a store), after-sales service or product support (online, by ‘phone, on site), training (online, by ‘phone, on site), the warranty (limited or all-inclusive, short or long duration), and the options for upgrading (firmware, trade-in for a newer model).

The way you assemble the piece parts of this ‘whole product’ is vitally important. Offering different sizes or colours opens up options for buyers for whom a standard version is limiting. Designing the packaging so it helps protect the product when not in use can be very valuable to the buyer. Different pricing models directly impact affordability. Manufacturers often overlook payment terms: offering generous terms may ease purchase – or lack of them may hinder it. Providing instruction manuals in digital versions means they are always available on the Web, even if the printed version is lost, while creating instructional videos adds a new level by showing the user the actual steps.

Case in point, one leading maker of computers gained market share when it changed the payments terms to make it easier for corporate buyers to acquire the product, not by designing in the very last CPUs.

The founder of a startup should validate the mix of attributes of the whole product before product launch. The way to establish the optimum mix is to talk with real customers. Allowing them to compare one bundle of elements against another will tell to you what appeals or turns off potential buyers. Doing so might reveal levels of product that can be offered at launch, or could be considered for the product road map for later release (especially with respect to add-ons, upgrades and accessories). It is easier to adjust the mix before you go-to-market, than to have to fix them afterwards.

Lindsay Powell is a Partner and Co-founder of TYLIPH Partners, which offers its clients access to people with actionable insights to position new tech companies for long-term success.

© Tyliph Partners |